As Jason Springs, professor of religion, ethics, and peace studies, watched Black Lives Matter protests sweep the nation last summer, he felt an urgent need to adjust his fall semester class to academically engage the movement of the moment.

Many courses in peace studies and related departments focus on the study of historical social and political movements, and Springs thought that the protests of 2020 provided a unique opportunity to study nonviolence in an explicitly relevant and present context.

“I wanted to design a full-fledged class to engage these current events in their immediacy and examine them comparatively with the Civil Rights movement,” says Springs. “The focus of the class is on processes by which nonviolence intermingles with forms of more explicit struggle and tip into forms of violence for transforming a society to be more just.”

In Springs’ course, called Revolutionary Violence vs. Revolutionary Non-violence in the Black Lives Matter Uprisings of 2020, the class readings featured a combination of recent articles, editorials, and studies on the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, as well as writings from Civil Rights activists that included James Baldwin and Stokely Carmichael.

Springs says that finding similarities and differences between the two movements is one of the fundamental goals at the heart of the course, and he wanted his students to understand the living legacies and voices of the 1960s.

His course also challenged the “romanticized appeal” of the Civil Rights movement, showing the realities of the nonviolent protests of twentieth-century America. Students analyzed sociological data on contemporary protests, which Springs says show a “[consistent, almost shocking]” trend of nonviolence.

“It’s a way to take political theory and peace studies concepts, and instead of having just an introductory understanding, you’re applying it to something super relevant and important,” says Francesca Masciopinto, a first-year student who took Springs’ class. “[We studied] Civil Rights, Martin Luther King Jr., Black Power, and political theory—and it’s so interesting to see these historical movements when we’re living through a historic moment.”

Another recently introduced course in the American studies department, Civil Rights in America, gave students a full semester to study the writings of leaders and activists of the 1960s alongside contemporary books such as How to Be An Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi and The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander.

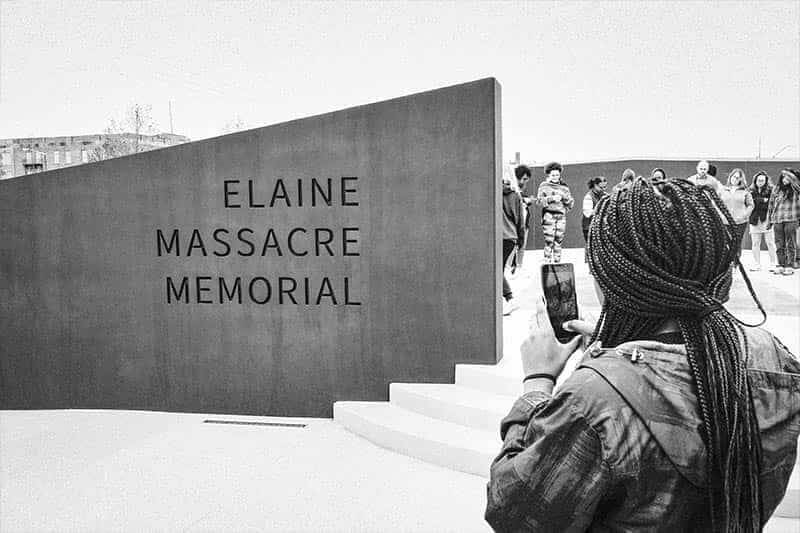

Alongside the instructional nature of the course, there was an experiential learning component offered during the first iteration of the class. Last spring, a group of students in the course went on a bus tour throughout the American South to visit historic landmarks from the Civil Rights movement, including the spot where Dr. King was assassinated, the site of Emmett Till’s murder, the Lynching Memorial, and Birmingham, AL.

The students also had the opportunity to speak to people in the south who had lived through many of the now-famous marches and protests.

“Hearing testimony from people alive during the Selma marches was really cool, and seeing their hope amongst all the bleakness of the world and that they could still be hopeful for the end of injustice was really powerful,” says Hailey Oppenlander, a junior who took the course in spring 2020. “Being in the physical space brought a lot of things to life. It was the last place I went before we went into lockdown, so that really stayed with me all summer.”

The creator of the class, Assistant Teaching Professor Peter Cajka, decided to teach the class so that students would be able to listen to Black voices. He says modern American culture is impossible to understand without centering racial violence and the efforts to fight it, which the class studies through a variety of black writers and activists who tried to change the system.

“Going into discussions about racial justice this summer, it was nice to have background and context on these issues, and to have read some of the books people were talking about. I felt prepared to grapple with these issues with the rest of the world,” says Oppenlander.

Both of these courses challenged students to look at issues that are affecting them and the country in which they live while engaging within the greater context of civil rights in America.

Springs says that the discussions surrounding nonviolence in both its practical and conceptual uses can sometimes be challenging in class because of students’ proximity to the topics of discussion.

“We have to be sensitive to student experiences while recognizing that we have to engage these things in their full gravity,” says Springs. “It’s one thing to study the example of Emmett Till and the powerful impact that his family’s witness had, but when you talk about the murder of George Floyd, it’s a very live experience and issue.”

Springs hopes his students see that “we’re not in completely uncharted territory.” He wants to push back against the narrative that the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s was a perfectly peaceful movement, while studying its internal diversities and complexities.

He also hoped that his students would leave the class with an understanding of their place in the “living, evolving enterprise” of U.S. democracy, and the ways in which democracy can be transformed through political nonviolent action to become more just.

“This is a really important class to have in the Notre Dame curriculum,” Masciopinto affirms. “It shows people’s commitment to addressing current issues and being able to face them and talk about them rather than pushing them under the rug.”

Learn More

- Follow students' travels through the American South via Retracing the Route of Freedom.

- Check out the fall 2021 peace studies courses.

- Explore the Center for Social Concerns, a campus hub for community-engaged learning.